Osmosis is one of those scientific principles that quietly governs countless processes around us, from how plant roots absorb water to how human cells maintain their shape. Many learners encounter the phrase “according to the rules of osmosis a system will…” and feel that the idea is incomplete or abstract. In reality, the rules of osmosis describe very specific, predictable system behavior rooted in physics, chemistry, and thermodynamics.

This article explains what a system will do according to the rules of osmosis, why it behaves that way, and how this principle applies in both living and non-living systems. We’ll move from simple definitions to deeper scientific reasoning, using clear language, practical examples, and modern biological context.

Fundamentals of Osmosis

What Is Osmosis? (Clear Definition)

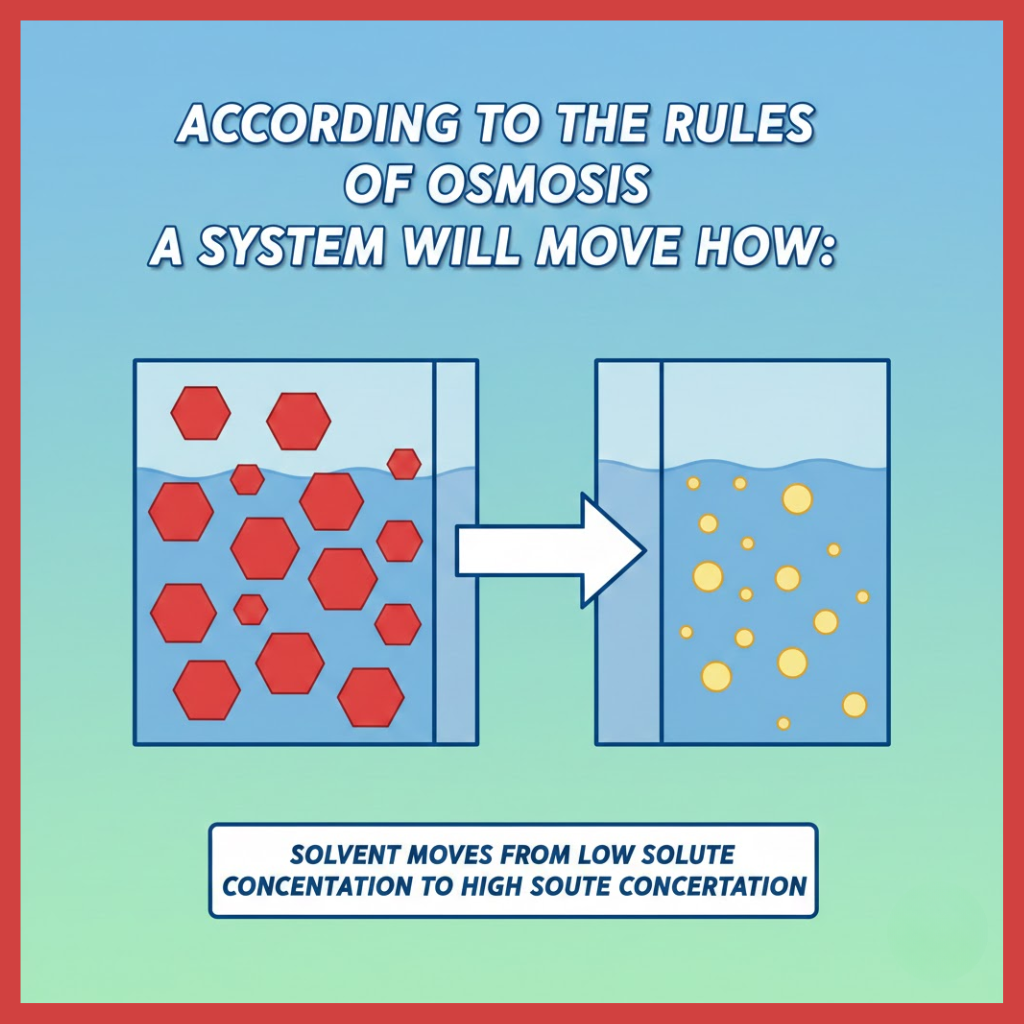

Osmosis is the passive movement of a solvent, usually water, across a semipermeable membrane from a region of higher water potential (lower solute concentration) to a region of lower water potential (higher solute concentration) until equilibrium is reached.

In simple terms, water moves to where it is “needed” to balance concentration differences.

This process:

- Requires no external energy

- Depends on a semipermeable membrane

- Continues until osmotic equilibrium is achieved

Also read: Who Delivers Your Offer to the Seller Framework Explained?

The Core Rules Governing Osmosis

According to the rules of osmosis, a system will behave based on three fundamental conditions:

- Presence of a semipermeable membrane

The membrane allows solvent molecules (like water) to pass but restricts solute particles. - Existence of a concentration gradient

There must be a difference in solute concentration on either side of the membrane. - Passive transport toward equilibrium

Water moves down its chemical potential gradient until balance is achieved.

If any of these conditions are missing, osmosis does not occur.

According to the Rules of Osmosis, How a System Behaves

Direction of Solvent Movement

According to the rules of osmosis, a system will always move solvent molecules from an area of lower solute concentration to an area of higher solute concentration, provided a semipermeable membrane separates them.

This direction is not random. It is driven by:

- Water potential difference

- Chemical potential of water

- Entropy-driven transport

Water flows to dilute the more concentrated solution, reducing the imbalance.

Net Solvent Flux and System Balance

At the molecular level, water molecules move in both directions. However, net solvent flux occurs toward the side with higher solute concentration. This continues until:

- Osmotic pressure balances the concentration gradient

- The system reaches dynamic equilibrium

- Free energy is minimized

At equilibrium, water still moves, but there is no net change.

The Role of Semipermeable Membranes

Why Membranes Control Osmosis

A semipermeable membrane is central to osmotic behavior. It creates selective permeability, allowing water molecules to pass while restricting solute particles.

Examples include:

- Cell membranes are made of phospholipid bilayers

- Synthetic dialysis tubing

- Plant cell walls combined with membranes

Without selective permeability, diffusion would occur instead of osmosis.

Membrane Selectivity and System Outcome

The permeability coefficient of a membrane influences:

- Speed of osmotic flow

- Rate of equilibrium achievement

- Degree of system stability

Highly selective membranes produce more predictable osmotic behavior, while leaky membranes may reduce or disrupt equilibrium formation.

Concentration Gradients and Osmotic States

Hypotonic, Hypertonic, and Isotonic Conditions

According to osmotic rules, system behavior depends on solution types:

| Water leaves the system | Solute Concentration | Water Movement |

|---|---|---|

| Hypotonic | Lower outside | Water enters system |

| Hypertonic | Higher outside | Water leaves system |

| Isotonic | Equal | No net movement |

These states explain why cells swell, shrink, or remain stable.

What Happens at Osmotic Equilibrium

Osmotic equilibrium occurs when:

- Water potential is equal on both sides

- Osmotic pressure is balanced

- Net solvent movement stops

Importantly, equilibrium is dynamic, not static. Molecules continue moving, but system-level balance is maintained.

Thermodynamic Explanation of Osmosis

Entropy and Free Energy in Osmosis

Osmosis is not driven by “need” but by thermodynamics. Water moves to maximize entropy and minimize Gibbs free energy.

Key drivers include:

- Chemical potential gradient of water

- Entropy-driven solvent movement

- Free energy minimization

This explains why osmosis is a passive transport mechanism.

Chemical Potential of Water

The chemical potential of water is lower in solutions with high solute concentration. According to the rules of osmosis, a system will move water toward regions of lower chemical potential to restore balance.

This principle applies universally, whether in cells or non-biological systems.

Osmosis Compared to Other Transport Processes

Osmosis vs Diffusion

Although related, osmosis and diffusion are not identical:

| Feature | Osmosis | Diffusion |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | Semipermeable membrane | Any medium |

| Substance moved | Solvent (water) | Solute or solvent |

| Direction | Water potential gradient | Concentration gradient |

Osmosis is a specialized case of diffusion involving membranes.

Osmosis vs Active Transport

Active transport:

- Requires energy (ATP)

- Moves substances against gradients

- Uses transport proteins

Osmosis:

- Is energy-neutral

- Moves solvent passively

- Requires no cellular input

Understanding this distinction is crucial for biology and physiology.

Osmosis in Biological Systems

Osmosis in Animal Cells

Animal cells rely on osmotic balance to maintain shape. For example:

- Red blood cells swell in hypotonic solutions

- Shrink in hypertonic environments

- Remain stable in isotonic conditions

Failure of osmotic regulation can cause cell lysis or dehydration.

Osmosis in Plant Cells

Plant cells use osmosis to maintain turgor pressure. Water entering the vacuole:

- Keeps plants upright

- Supports growth

- Enables nutrient transport

The rigid cell wall prevents bursting, creating controlled system stability.

Osmosis in Non-Biological and Real-World Systems

Osmosis Beyond Living Cells

Osmosis is not limited to biology. It occurs in:

- Water purification systems

- Desalination membranes

- Food preservation processes

Reverse osmosis systems intentionally apply pressure to counter osmotic flow, demonstrating practical control over the process.

Industrial and Medical Applications

Applications include:

- Dialysis machines

- IV fluid formulation

- Pharmaceutical solution design

- Food processing and preservation

These systems rely on predictable osmotic behavior for safety and effectiveness.

Factors Affecting Osmotic Flow

Several variables influence how a system behaves under osmotic rules:

- Solute concentration imbalance

- Temperature

- Membrane permeability

- Pressure differences

- Type of solute particles

Changes in any of these can alter the rate or outcome of osmosis.

When Osmosis Does Not Behave Ideally

Edge Cases and System Failures

Osmosis may deviate from ideal behavior when:

- Membranes are damaged

- Solutes cross the membrane

- External pressure disrupts equilibrium

- Non-ideal solutions are involved

Understanding these limitations prevents common misconceptions.

Common Misunderstandings About Osmosis

Some frequent errors include:

- Believing osmosis “stops” completely at equilibrium

- Confusing diffusion with osmosis

- Assuming energy is required

- Ignoring membrane selectivity

Clarifying these points strengthens conceptual understanding.

FAQS: According to the rules of osmosis a system will

What happens to a system according to osmosis?

A system will move solvent across a semipermeable membrane to reduce concentration imbalance and reach equilibrium.

Why does osmosis stop at equilibrium?

It doesn’t stop entirely; net movement stops because opposing forces balance.

Is osmosis always about water?

Primarily, yes, because water is the most common biological solvent.

Can osmosis occur without a membrane?

No, without selective permeability, the process becomes diffusion.